I did what all good historians do and gathered together my sources. In the process of moving, I have had occasion to go through a lot of old stuff. It’s amazing what I have kept, or not thrown out. Perhaps more amazing what my parents have kept, or not (yet) thrown out. If I was going to help inspire these foundlings with history I needed not to give them a career lesson (and I would not exactly be a great exemplar) but just to understand the satisfaction that understanding the past can bring. So where better than to start with self, family and locality.

‘A little bit of TRUE information can be used to make people believe something which is UNTRUE’

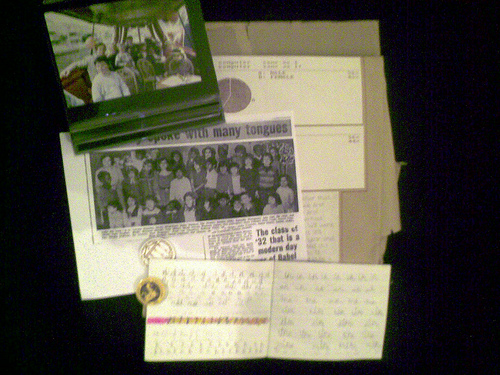

My bag of sources contained:

- A newspaper article from about 1984 headlined ‘And they spoke with many tongues’, probably from the Sunday Express no less, about the school and the 32 languages spoken by its pupils, ‘a modern day tower Tower of Babel’. Our headmistress was an early exponent of the school’s cosmopolitanism but stressed how a few weeks at the school got everyone speaking and reading a good standard of English.

- My first junior school report (handwritten).

- A selection of photographs, of family, school outings and assemblies and friends, including one of my father as a little boy who had also attended the school.

- My grandfather’s standard issue heliograph.

- My first swimming certificate (which one pupil mistook for an ‘achievement award’).

- A letter of thanks from the Queen for a poem I wrote for her 60th birthday.

- The programme from my final year school play, signed by our teachers.

- Some badges relating to notable local places that exist or no longer exist (e.g. the long lamented London Toy and Model Museum).

- My first story book from the equivalent of Reception/Year 1 (age 5-6).

- My handwriting book. I was banking on them still having a handwriting book as an example of things that don’t change.

- The school’s first ever computer-based project, undertaken by a friend and me in our final year (equivalent of year 6) in 1989. Print-outs of pie-charts and summary reports were mounted on what was once purple sugar paper. It is now faded and torn but one of the most interesting personal and social documents I have. It was based on a survey made of computer use by girls and boys in our year. If ever I can pinpoint my attitude towards history and historians it is the conclusion we wrote, clearly with a little help from our teacher: ‘A little bit of TRUE information can be used to make people believe something which is UNTRUE’.

- A copy of a book I wrote on medieval food and feasting.

- A book on the local area.

- Postcards of Edwardian images of people who worked in the local area.

I think it is fair to say that this would rival any loan box the school could have got hold of and yet all the items are relatively mundane, relatively for someone to procure. Without my museum or archive hat on I could also let them touch the things, although I was careful to guide them to the notion that old things are more fragile and therefore need a little more care. My intention was simple. By relating my own life and that of my family to both the school and locality and then to these documents and objects I wanted to show how studying history was as much finding out who we are and the truth of our past as it was to know what the Romans ate for breakfast.

Both classes I took part in had just done the Romans and had some rudiments of local history. A pupil in the first glass greeted me with an in-character Roman Centurion soliloquy. I was seriously impressed. After a brief introduction as to who I was, my connection with the school, and why I love history started the many and several questions. ‘How old are you?’, ‘do you know what carpe diem means?’ [yes really], ‘how old was Claudius when he invaded Britain?’ [gulp], ‘why did you want to become a historician?’ and ‘when did William the Conqueror burst?’ [excuse me?]. Following these and several more, they were split into groups to come in turn to my history table.

The groups in the first class were most curious about my story book and handwriting book. Others pored over the photographs, particularly impressed with our school outing to Buckingham Palace and the photography of one of my school assemblies. One pupil thought it looked exactly the same, the other thought it was totally different. Go figure how differently we interpret the same sources. The first ever school computer project was however beyond them, perhaps more of interest to the teachers. They were not familiar with pie charts and they couldn’t quite understand why it was such a big deal, ‘I have a computer at home’. Quite so. A photograph of my great-grandmother, grand mothers and mother caught their eye, particularly when I explained that I had been named after my great-grandmother. One girl piped up that she was named after her grandmother and a light switched on. I asked them to read the date on the letter from the Queen and work out how many years ago it was. 1986 to 2011 presented them a problem.

At an age when we all remember the almost interminable summer holidays, working out how many years ago that was was something mind-blowing. One of them eventually got to 25 years but the appreciation of the passing of time was clearly still not there. It was all I could do to get them to figure out that I was four times their age. This made me appreciate most acutely how hard it is to teach chronology and the scale of time to people who have existed for such a short time. I could only convey distance in time by emphasising the number ‘fifty years ago!’ ‘three HUNDRED years ago’ ‘I’m not that old’.

A better appreciation of the passage of time came with discussing what in the local area had changed and what hadn’t. The big shopping centre that was closed for most of my early life, previously a department store (that took some explaining), reopening on my last day at the school (and here is the badge we were given), the toy museum that is now no longer next to the school (alas from all of us), the library which they all still go to, that I also went to, the swimming pool we learnt to swim in, the carnival we went to. For some of them it may take many years for the ideas to be absorbed. This was history but it wasn’t the kind of history they knew or would even recognise.

The second class’s personalities were completely different. They were most interested in my book and generally about food, and of course, the Romans. ‘Did you know that July is named after Julius Caesar?’, ‘Did all Romans wear togas?’, ‘how old are you?’, ‘when was paper invented?’ Showing the group my photographs I asked how long they thought there had been cameras and photographs. Estimates included 5000 years, 2000 years, 10 years and 2 years until a small voice hesitantly hazarded 100 years. Ok, let’s not quibble about 50 years. What got them all singing was the shock that medieval Europeans did not eat crisps, chocolate, tomatoes or sweetcorn. A veritable travesty they thought. An appalling affront to their sensibilities. When asked where they thought the potato came from, keen responses included ‘England’, ‘Asia’, ‘Pakistan’, ‘Australia’ and finally ‘America’. Finally they had a flavour of when the Middle Ages were and largely what it was lacking. They also correctly identified the epoch as being after the Romans.

Class 2’s group work was not dissimilar to the first. They were enthralled by my exercise books and complemented me like the previous class had on my handwriting. Even the teacher said that she couldn’t believe how high the standards were. I didn’t want to enquire further. This group were more interested in the objects, the badges and heliograph. One of their fathers was in the army and they understood the concept of morse even though they hadn’t yet been taught it. One pupil was so enamoured with the badges that she scooped them up and admired them livingly on her jumper before asking where each came from. Another one asked if I drew all the pictures in my book on medieval food. I thought it beyond the pale to explain manuscript illumination in such a short space of time so just relented and said someone else did them.

Most of all both classes were pleased at being able to identify me in the Tower of Babel newspaper article. One of them even said I looked nice in the picture. Historians in the making?

I cannot predict what the learning outcomes for these children will be. There is no instant result in this kind of learning. It is what it is. I remember certain episodes in my primary school education that had a definite effect on me and my choices but I didn’t know it then.

1 comment

Comments are closed.